«I have never worked on such a sought-after topic before»

Article from the Info Day Magazine 2022

Environmental engineer Tamar Kohn has been a professor at the EPFL since 2007. She heads the Laboratory of Environmental Chemistry (LCE) there and studies how viral pathogens behave in the environment. In the following, she provides insights into the Covid monitoring in wastewater that she co-initiated.

Ms Kohn, in early January 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 virus was identified in China. Already in February, you and your team took the first wastewater samples to test them for the virus. How was it possible to respond so quickly?

Thanks to a postdoc who has been working with me on viruses in wastewater since 2018, we already had the expertise in the laboratory and knew how to detect viruses. When the coronavirus emerged in China, I was contacted by the Head of Eawag’s Human Health Pathogens research group, Tim Julian, with whom I had collaborated a lot before. He is primarily concerned with the question of how pathogens are transmitted through the environment. We also included Christoph Ort from Eawag in the ad hoc team, because as head of the pollutants in sewers group, he knows the wastewater scene in Switzerland very well. All he had to do – to put it simply – was to pick up the phone and the samples came. Thanks to this interdisciplinary expertise, we were able to start right away when everything hit the fan in Switzerland.

Did you act on behalf of the authorities or on your own?

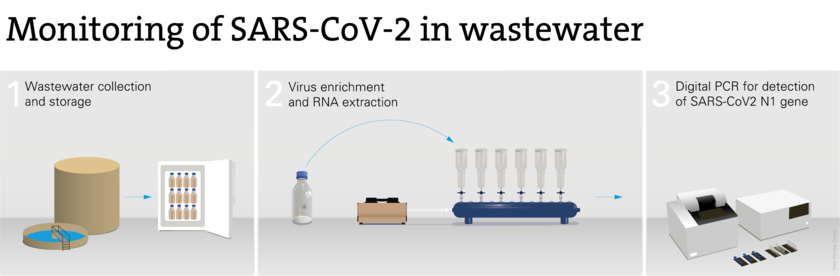

It was the initiative of our research team. In the environmental engineering field, it was clear from the beginning that the detection of Covid-19 in wastewater would be a possible method for monitoring the pandemic. An international network was quickly established among the researchers. The difficult thing was to make the method palatable to the public health people as well. Although the concept has been applied internationally to the monitoring of polio outbreaks for a long time, they tend to work qualitatively and with random samples, whereas we do high temporal resolution and quantitative monitoring. We had to do some preliminary work to show that the method is something that has value and that it is worth investing in. After about a year, the FOPH stepped in and then financed a research project for us to monitor six WWTPs in Switzerland.

What are the advantages of virus detection in wastewater compared to clinical testing?

This allows us to monitor the entire dynamics of the pandemic independently of the population’s willingness to test, and to see, for example, where the virus concentration decreases after a given policy measure or where it stays the same. Now that the tests are declining, we can still see in the wastewater how the pandemic is behaving. We can also detect at an early stage when new virus variants appear in Switzerland, provided it has already appeared somewhere else in the world. On the other hand, it is very difficult to find something if you don’t know where to look for it. This is where the early warning system reaches its limits.

What were your personal highs and lows in this research project?

One highlight was that the cooperation worked really well, firstly internationally, but also nationally, for example with colleagues from the ETH Zurich, but also with cantons and the WWTP staff. It was also gratifying that the public was very interested in our method, especially when we found the alpha variant before it was clinically detected. I have never worked on a research topic where you are in such demand and so close to the current events of the day. On the other hand, it was a lot of work, especially during the lockdown when our Covid team was still small. We had to rely on labs that were supposed to be closed, had to switch to online lectures at the same time and some had small children that we were supposed to homeschool. These first months were extremely demanding.

What is the next step for Covid monitoring and will it possibly be extended to other infectious diseases?

Our research project will probably run until the end of 2022. In parallel, the FOPH has now extended Covid monitoring to over 100 WWTPs throughout Switzerland. We are therefore in a good starting position for the long-term monitoring of wastewater. It took some time to get the logistics in place and to build up a network. But this work is now done and it would be easy to continue. There are also international efforts to continue wastewater monitoring, not only for Covid, but also, for example, for the next influenza outbreaks. Plus, there are various other diseases that could be monitored effectively this way. I very much hope that Switzerland will utilise wastewater monitoring in the future to monitor and analyse infectious diseases in the population generally.

Collecting wastewater samples at Zurich’s Werdhölzli wastewater treatment plant.

(Photo: Esther Michel, Eawag)

Created by Christine Huovinen for the Infoday Magazine 2022